| The Cancún climate summit proved an unexpected success, though critical issues remain unresolved. Newswatch editors Sarah Granich and Mick Kelly report on the lead-up to the summit and on its outcome. |

As the final negotiations before the Cancún climate summit took place in Tianjin, China, during October 2010, Christiana Figueres, executive secretary of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, urged Parties to the climate treaty to "move beyond their national interests in pursuit of a common good." The aim would be to focus on manageable aspects of the climate negotiations at the December summit, with contentious issues to be resolved at a later date.

Tension between China and the United States threatened to overshadow the Tianjin talks, with China warning that there would be no compromise on the interests of developing countries. "We are losing trust and confidence," said foreign ministry representative Huang Huikang. The Chinese response was triggered by comments by Jonathan Pershing, United States deputy special envoy on climate change, who said that the United States was disappointed with the pace of the negotiations and might pursue an alternative to the United Nations process. Pershing also accused some countries of attempting to "relitigate" agreements embodied in the Copenhagen Accord. "A developed country I won't name hasn't done a job for itself," said Xie Zhenhua, China's head negotiator. "It has not provided financing or technology to other countries, yet it asks them to accept stringent monitoring and voluntary domestic actions. It's totally outrageous. It's quite unacceptable," he continued.

As the Tianjin negotiations ended, Figueres was pleased that participants had come closer to defining what could be achieved at the forthcoming summit in Cancún. "This week has got us closer to a structured set of decisions that can be agreed in Cancún. Governments addressed what is do-able in Cancún, and what may have to be left to later," she said. Action that could be agreed at the summit was about turning "small climate keys that unlock very big doors," generating a new level of climate action among rich and poor, business and consumers, governments and citizens. "If climate financing and technology transfer make it possible to give thousands of villages efficient solar cookers and lights, not only do a nation's entire carbon emissions drop, but children grow healthier, women work easier and families can talk, read and write into the evening," she said. This is about real people being given the opportunity to take control of their future stability, security and sustainability, she added.

Prospects for Cancún were eroded with Republican gains in the mid-term elections in the United States undermining plans for a domestic cap and trade approach to mitigation and hence participation in international efforts. Nevertheless, the European Union, planning to cut carbon emissions to 20 per cent below 1990 levels over the next ten years and considering further action, held to its position. "The goal for Canćun remains a balanced set of decisions which keep up the momentum toward an international framework to keep global temperature increase below two degrees Celsius," said José Manuel Barroso, president of the European Commission.

In November 2010, fifteen countries, meeting at the Tarawa Climate Change Conference in Kiribati, signed the Ambo Declaration. The Declaration calls for decisions on an "urgent package" for concrete and immediate implementation to be agreed to at the Cancún climate summit to assist those in most vulnerable states on the frontline to respond to the challenges posed by the climate crisis. The aim of the meeting was to hold a consultative forum between vulnerable states and their partners, creating an enabling environment for multi-party negotiations under the auspices of the climate treaty. Colonel Samuela Saumatua, Fijian environment minister, said that the location of the meeting was ideal for dialogue. "The spirit of discussion was very helpful, very Pacific," he said. "It's a far cry from Copenhagen, and here people suggested things, instead of saying you can't have that, they said it may be better to look at it this way. So that's the spirit of things." The Declaration was signed by Australia, Brazil, Canada, China, Cuba, Fiji, Japan, Kiribati, Maldives, Marshall Islands, New Zealand, Solomon Islands and Tonga. Kiribati president Anote Tong reported that he was disappointed that the United States and the United Kingdom opted out of the declaration by taking up observer status.

Small Island States announced that they want an end-2011 deadline for a new climate agreement. "In the case of climate, emergency requires speed," said Dessima Williams of the Alliance of Small Island States. "Anything that is not concluded in Cancún should not be put off into the indefinite future but could easily and should be referenced to South Africa [the 2011 climate summit]," she argued.

|

|

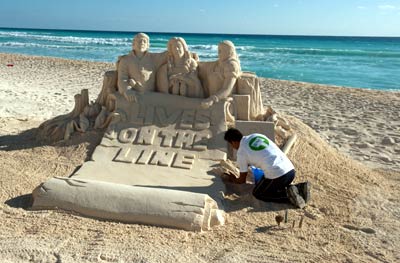

Mexican farmers' sand sculpture at the

Cancún climate summit

© Oxfam International |

As the summit approached, Figueres remained confident of a positive outcome. "Everything I see tells me that there is a deal to be done," she said. What might emerge is a set of interlocking agreements. "Countries have actually learned for themselves... that there is no such thing as one all-encompassing solution," Figueres said. "They also seem to be setting out to develop the building blocks upon which they can build realistic action on the ground, because countries really need results on the ground right now. And I don't see them veering away from that in any sudden way."

"Climate change is an issue that affects life on a planetary scale," said Mexican president Felipe Calderón as the Cancún climate summit got underway. "What this means is that you will not be here alone negotiating in Cancún. By your side, there will be billions of human beings, expecting you to work for all of humanity," he continued. Around 15,000 people participated in the summit.

Japan created widespread consternation in the summit's opening days when it announced that it would not support extension of the Kyoto Protocol from 2012. Environment minister Ryu Matsumoto described the treaty as "outdated" as it only covered nations responsible for 27 per cent of world emissions. Japan wants a global treaty. "It does not make sense to set the second commitment period under the Kyoto Protocol as the current Kyoto Protocol is imposing obligation on only a small part of developed countries," said Japanese negotiator Hideki Minamikawa. "With this position, Japan isolates itself from the rest of the world. Even worse, this step undermines the ongoing talks and is a serious threat to the progress needed here in Cancún," said Yuri Onodera of Friends of the Earth Japan. Developing nations see progress on the future of the Kyoto Protocol as a prerequisite for a broader global agreement.

The atmosphere during the negotiations was, in the main, far more constructive than at the previous summit. "There is more camaraderie than I saw in Copenhagen, more dialogue and much more intense engagement between the United States and China, and less shadow boxing," commented Indian environment minister Jairam Ramesh.

After over-running on the final day, the talks ended with two major agreements. The developed nations, recognizing their historic responsibility, "must take the lead in combating climate change and the adverse effects thereof," states the agreement on long-term cooperative action. Developing countries, for their part, will take "nationally appropriate mitigation actions in the context of sustainable development," subject to adequate financial and technical support. A compromise agreement was reached on an international inspection regime for these nations, a development that China had opposed. Under the second agreement, the Kyoto Protocol will continue beyond 2012, though critical details, such as national emissions targets, have still to be negotiated and there must remain doubt regarding the future of the Protocol. The overarching goal of the two agreements is to hold the increase in global average temperature to below two degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels. This goal will be reviewed after five years and the need to restrict the temperature rise to 1.5 degrees Celsius will be considered.

Two decades on, adaptation is at long last given equal weight with mitigation in the international response to the threat of climate change. The wide-ranging Cancún Adaptation Framework covers: planning and implementing adaptation actions; impact, vulnerability and adaptation assessment; strengthening institutional capacities; building social and ecological resilience; enhancing disaster risk reduction strategies; measures regarding climate change-induced displacement, migration and planned relocation; development and transfer of technologies, practices and processes and capacity building; strengthening data, information and knowledge systems, education and public awareness; and improving climate-related research and systematic observation. A process will be established that enables least developed country nations to formulate and implement national adaptation plans.

|

|

Indigenous peoples' caucus at the Cancún

climate summit

© Oxfam International |

The Green Climate Fund will provide "scaled-up, new and additional, predictable and adequate funding" for developing country activities and will be run by developing and developed countries, resolving contention regarding the role of the World Bank. Support will rise to a goal of US$100 billion a year in 2020. Agreement has also been reached on finance to support developing countries limit emissions by forest protection.

In his closing address, Mexican president Felipe Calderón declared the conference a success, saying that the agreements "altered the inertia and have changed the feeling of collective powerlessness for hope in multilateralism" that had settled over recent negotiations. The role of executive secretary Figueres, in pushing through the two agreements was highly commended. She was described as a "goddess" by Ramesh.

Reaction to the twin agreements reached at the Cancún summit was generally positive. "We have strengthened the international climate regime with new institutions and new funds," said European Union climate commissioner Connie Hedegaard. "Market participants didn't really expect much and what we saw was a clear political commitment," said Martin Schulte, a director at First Climate. "We've got out of the complete standstill," he concluded.

Jake Schmidt of the Natural Resources Defense Council in the United States, citing progress on emissions reductions, greater transparency, forest preservation and the creation of the green fund, described the agreements as a detailed set of visionary, yet pragmatic principles that provide a solid foundation from which to build upon, "The Cancún Agreements, combined with the efforts of millions of people around the world working at the personal, local, state and regional levels to deal with this problem, signify real progress," he said. There was a very positive response to the possibility that China will accept a degree of international verification of its emissions control. "It's a huge step in the right direction," said Fred Boltz of Conservation International.

Saleemul Huq from the International Institute for Environment and Development, a Tiempo editor, commented that "we're on a very good start" with the Green Climate Fund. "The two things that we did achieve in Cancún, against expectations somewhat in fact, we now have the new climate fund and countries have started pledging," he explained.

Agreement on Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation (REDD) was a major outcome of the meeting. Greenpeace spokesman Steve Campbell said that the REDD mechanism could be a major step forward for forests, though "the devil is really going to be in the detail." He was pleased that forests will not be included in carbon markets. Ben Powless from the Indigenous Peoples' Forum on Climate Change welcomed the forest agreement but warned that the language on safeguarding indigenous peoples' rights was weak. "That still maintains the possibility to privatize a large part of our natural resources, our lands and territories. And really the ones who would suffer from that would be indigenous communities as well as biodiversity," he said.

© 2011 Lawrence Moore

There were reservations regarding the lack of any concrete mitigation commitments in the Cancún agreements, with no global emissions reduction target for 2050, no target for a peaking year and no firm emissions reduction targets for developed countries. As Sunita Narain from the Centre for Science and Environment in India commented, "the move is to replace the [existing] regime with voluntary targets for all." This issue looks set to dominate negotiations leading to the 2011 summit in South Africa.

In a letter sent to the Mexican president, Mohamed Nasheed, president of the Maldives, pledged his country's backing for the Cancún Agreements and congratulated Calderón for his government's "remarkable achievement in successfully brokering the balanced package of decisions."

In the summit's aftermath, Figueres called for the rapid launch of the new institutions and funds covered by the agreements to confirm that a new area of international cooperation on climate change is an established fact. "Many millions of the poor and vulnerable people of the world have been waiting years to get the full level of assistance they need. Industrialized nations will soon have a clear, comprehensive structure into which they can direct the funding they have promised," she said. She asked all countries, particularly the industrialized nations, to deepen their emissions reductions commitments. "Cancún was a big step, bigger than many imagined might be possible. But the time has come for all of us to exceed our own expectations because nothing less will do."

Existing pledges and promises to control national emissions, if fully realized, could deliver around 60 per cent of the reductions needed to limit the rise in global temperature to two degrees Celsius over the 21st century, according to a recent report from the United Nations Environment Programme. This leaves, though, a large 'gigatonne gap' still to be addressed.

Sources

The Newswatch archives for 2010 and 2011 cite news articles and press releases used in preparing this report.

Further information

The Tiempo Climate Cyberlibrary provides weekly coverage of climate news. For detailed discussion of all climate negotiating meetings, visit Earth Negotiations Bulletin.