Tiempo Climate Cyberlibrary

Gender and Climate Change - a Forgotten Issue?

- Tiempo archive

- Complete issues

- Selected articles

- Cartoons

- Climate treaty

- Latest news

- Secretariat

- National reports

- IPCC

About the Cyberlibrary

The Tiempo Climate Cyberlibrary was developed by Mick Kelly and Sarah Granich on behalf of the Stockholm Environment Institute and the International Institute for Environment and Development, with sponsorship from the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency.

While every effort is made to ensure that information on this site, and on other sites that are referenced here, is accurate, no liability for loss or damage resulting from use of this information can be accepted.

|

Ulrike Röhr discusses the historical lapse in assimilating gender issues in the climate change debate and the urgent need to undertake research and analysis on this issue. The author is director of genanet - focal point gender, justice, sustainability, which aims to integrate gender justice within environmental and sustainability policies. Her primary areas of responsibility are gender issues in energy and climate change. |

Until very recently, gender issues have not played a major role in climate protection discussions. This is surprising given the situation that equity in general, especially between South and North, is regularly on the agenda and is a key issue in the climate change negotiations.

Only in the past couple of years have discussions about gender during Conference of the Parties meetings to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) been raised. At the Ninth Conference of the Parties, held in December 2003 in Milan, Italy, a network of people interested in gender issues was established. The network organized two workshops on gender and climate change at the Tenth Conference of the Parties, held in December 2004 in Buenos Aires, Argentina. Activities and discussions on gender are already planned for the Eleventh Conference of the Parties to be held in November and December this year in Montreal, Canada.

Thus, at the international level of climate change negotiations, gender issues are on the rise. Moreover, many projects in developing countries are now addressing the different situation of women and men respective to their different vulnerabilities to climate change. In the industrialized countries of the North, after an absence of activities on gender and climate change, it would seem that this issue is about to be discovered.

There are a number of activities already underway. A research project at the Institute for Social-Ecological Research in Germany is dealing with gender issues and emissions trading. City networks are contributing to increase the share of women in decision making in climate change policies. The Climate Alliance of European Cities coordinated the project Climate for Change: Gender Equality and Climate Change Policy. The regional government of Lower Austria has considered gender mainstreaming within their climate change programme. All of these activities are based on the premise that climate change policies will be more effective if more women are involved and if gender issues are addressed.

Against this background I want to look more closely at how climate change is tangent to gender relations - and vice versa.

Questions to be raised when dealing with climate change from a gender perspective are:

- Are there gender differences in the perception of, and the response to, climate change?

- Who is causing climate change, by which activities, and for what purposes? How is the polluter-pays-principle taken into account in mitigation and adaptation policies and measures?

- Are there gender differences as to what policies and measures are preferred and, if so, what are the reasons for these differences?

- Are women and men affected differently by the effects of climate change? What are the gender specific impacts of climate change and its resulting environmental damages?

- Are there gender differences in negotiations and decisions on climate change policy? How and to what extent are women participating when it comes to working out and deciding about climate protection programmes and measures? How do the results and programmes impact gender relations, for example, climate policy guidelines and directives at the national, the European Union and the international level?

|

|

© Corel Corporation |

Because there is an obvious historical lack of research, many of these questions cannot be answered at present. And not all these questions are similarly relevant in each region of the world. In the climate debate, questions linked to adaptation are more relevant in the South, while in the North questions connected to mitigation are more on top.

Gender and climate change in the South: adaptation

It is widely acknowledged that the negative effects of climate change are likely to hit the poorest people in the poorest countries the hardest. In other words, the poor are the most vulnerable to climate change.

Women form a disproportionate share of the poor. Seventy per cent of human beings worldwide living below the poverty line are women. In particular, in developing countries and communities that are highly dependent on local natural resources, women are likely to be disproportionately vulnerable to the effects of climate change. Climate change often impacts the areas that are the basis of livelihoods for which women are responsible, for example, nutrition and water and energy supplies. Moreover, because of gender differences in property rights, access to information and in cultural, social and economic roles, the effects of climate change are likely to affect men and women differently.

The effects of climate change on gender inequality are not limited to immediate impacts and changing behaviours but also lead to subsequent changes in gender relations. Spending more time on traditional reproductive tasks reinforces traditional work roles and works against a change in which women might begin to play other roles.

For instance, because women are primary care-givers in times of disaster and environmental stress, the occurrence of magnified burdens of care-giving is likely to make them less mobile. Also, since climate change is expected to exacerbate existing shortfalls in water resources and fuelwood, the time taken to fetch water or wood (which in most countries is the responsibility of women) will certainly increase women's workloads, thus, limiting their opportunities to branch out into other, non-traditional activities.

|

The network Gender in Climate Change has given the following example of the differential impact of a natural hazard on women and men: Following the cyclone and flood of 1991 in Bangladesh the death rate was almost five times as high for women as for men. Warning information was transmitted by men to men in public spaces, but rarely communicated to the rest of the family and, as many women are not allowed to leave the house without a male relative, they perished waiting for their relatives to return home and take them to a safe place. Moreover, as in many other Asian countries, most Bengali women have never learned to swim, which significantly reduces their survival chances in the case of flooding. Another clear illustration of the different vulnerabilities women and men face is offered by the fact that more men died than women during Hurricane Mitch. It has been suggested that this was due to existing gender norms in which ideas about masculinity encouraged risky, 'heroic' action in a disaster. |

To be successful, adaptation policies and measures within both developed and developing countries need to be gender sensitive. To understand the implications of adaptation measures for all people involved, it is necessary that all members of an adapting community are represented in climate change planning and governance processes.

During a drought in the small islands of the Federal States of Micronesia, the knowledge of island hydrology from women as a result of their land-based work enabled them to find potable water by digging a new well that reached the freshwater lens. Women, however, are often expected to contribute unpaid labour for soil and water conservation efforts yet are absent from the planning and governance processes. Equal involvement of men and women in adaptation planning is important not only to ensure that the measures developed are actually beneficial for all those who are supposed to implement them, but also to ensure that all relevant knowledge, (that is, knowledge from men and women) is integrated into policy and projects.

Gender and climate change in the North: mitigation

The participation of women in decision making, in planning and working out climate protection programmes is as important in the North as in the South. In the project Climate for Change, the involvement of women has been investigated, leading to the following results.

The relevant fields of action for climate protection such as energy policy, urban mobility and urban planning, are definitely male-dominated because of their technical focus. Among others, two initial questions arise. Firstly, who might profit if climate protection programmes lead to job creation? And secondly, what is the effect on the planning of measures and policies if they are almost exclusively planned from the viewpoint of one gender, whose background of experience usually excludes the work involved in caring and providing for others? Such questions should encourage us all to reflect on and discuss these important, everyday issues.

Up to now, there have been only few studies that have specifically addressed gender aspects in climate protection in industrialized countries. But there is a certain amount of data, especially from Germany, which points to differences between the sexes, and leads to the assumption that the priorities of women in climate protection may be different from those of men. The data lead to the following conclusions.

- Women and men perceive and assess risks differently, and that is also true for climatic change. More than 50 per cent of the women, but only 41 per cent of the men, classify climate change caused by global warming as extremely or very dangerous. Consequently, women are more strongly convinced than men that global warming is unavoidable in the next 20 to 50 years.

- Trust placed in the role played by environmental policy also varies according to gender. More women than men are sceptical that Germany can cope with problems resulting from climate change. Nonetheless, almost 62.9 per cent of the women, but only 53.8 per cent of the men, are in favour of a pioneer role for Germany in climate policy.

- These differing perceptions of climate change, and the political possibilities of reacting to it, affect each gender's motivation to protect the climate. Women are more willing to alter environmentally harmful behaviour. They do not rely as much on science and technology to solve environmental problems to the exclusion of lifestyle changes. As a result, they place a higher value on the influence exerted by each and every individual on preventing climate change.

- Studies show that women have a definite information deficit on climate politics and climate protection. This raises the question of how the subject matter is communicated. Is it slanted toward technically interested people? Do the selection of photographs and the layout suggest that the target group is male? Browsing through brochures and informational material, this often seems to be the case. These discrepancies are particularly noticeable with regard to the extent to which people are informed about the international climate negotiations. But despite their relative lack of knowledge, women seem to be more prepared for behavioural changes than men, as they recognize the urgency of the need for changes in behaviour. In many areas they are already adjusting their behaviour to meet this need, for example, by reducing their energy consumption, using more public transport and changing their nutrition and shopping habits.

- The instruments used to prevent climate change are probably also gender-biased. For example, how are economically differing preconditions taken into account in the design of these instruments? In Europe, women generally earn 28 per cent less than men, and 27 per cent of single mothers live below the poverty line.

In general, all these gender-specific differences are either due to physiological differences or, to a much greater extent and scope, to differences in social roles assigned to women and men and gender-specific identities in society. Gender roles and identities are linked to gender hierarchies in terms of opportunity and participation in power structures in society. When considering the issue of gender relations, one must, therefore, also always bear in mind the power relations associated with them.

Looking at climate change mitigation from a gender perspective we, last but by no means least, have to answer these questions. Who, primarily, is causing the problems of carbon dioxide emissions? Who gets the benefits? Why is the polluter-pays principle so little taken into consideration in climate change policies? There might well be a strong connection between gender relations, power relations and these questions that has not yet started to be discussed.

|

|

© Corel Corporation |

The outlook

As mentioned above, gender issues have not been recognized in the UNFCCC negotiations until now, although there was a very weak decision at the Seventh Conference of the Parties in December 2001 in Marrakesh, Morocco regarding the nomination of women in the bodies of the UNFCCC.

To improve this situation, some fundamental requirements have to be addressed immediately so as to provide a just and equitable approach to this issue.

Research and data. We do not know enough about gender aspects of climate change, particularly in the North. For example, with regard to climate protection measures, there is no gender analysis from a Northern perspective, only, in some aspects, from a Southern perspective. All climate protection measures and programmes and all instruments for mitigating climate change or adapting to climate change must be subject to a gender-focused analysis. All climate change-related data, scenarios, and so on, need to be disaggregated by gender. Gender-disaggregated data are particularly lacking for the developed world.

Relevant research needs to be developed and financed. This requires gender experts and climate researchers to engage in the issues, and it requires funders to support such research projects. Based on existing knowledge in the area of climate change as well as in other areas, specific suggestions for research projects can easily be developed and advocated.

Gender mainstreaming. Gender must be universally integrated into climate protection negotiations and policy making at national and international levels. The different needs, opportunities and goals of women and men need to be taken into account. The beginning post-2012 process offers an important opportunity.

Participation. Women must be involved in climate protection negotiations at all levels and in all decisions on climate protection. Representation by numbers is not enough. We need women represented and we need gender experts involved.

Information/publications. There is a general information deficit on climate protection and related policies. New information materials and strategies need to be developed. They need to include gender aspects, and they need to be targeted to group specific, including being tailored for women's information channels.

Monitoring. Gender mainstreaming of climate change-related research, policy making and implementation needs to be monitored at the national and international levels. This can be summarized within three main goals.

- Closing knowledge gaps relating to gender aspects of climate change in the developed world, for example, through research and the collection of gender-disaggregated data.

- Including more women and gender experts in climate protection-related negotiations and decision making at all levels.

- Integrating gender-related knowledge into policy making, implementation, monitoring, and communication strategies and materials.

The above-mentioned requirements are based on the paper Gender and Climate Change in the North: Issues, Entry Points and Strategies for the Post-2012 Process and Beyond which was written by Minu Hemmati for genanet - focal point gender justice and sustainability.

If any climate protection policy ignores the afore-mentioned as well as many other, proven or as yet only suspected, gender aspects, it cannot be accepted as sustainable, since it would have a counter-productive effect on gender equality. Without taking gender aspects into consideration, the task of preventing climate change will be difficult to achieve.

I am absolutely certain that gender-just participation and recognition of gender relations will lead to a more comprehensive view of climate change. The full diversity of social groups and their living situations are more likely to be taken into account. Children, the elderly and migrants, for example, will be taken into rightful account. This will, in turn, lead to improvement of the measures, and to a higher acceptance of gender issues amongst the global populace.

Further information

Ulrike Röhr, genanet - focal point gender, justice,

sustainability, LIFE e.V., Hohenstaufenstr. 8, 60327

Frankfurt am Main, Germany. Fax: +49-69-740842. Email:

roehr@life-online.de.

Web: www.genanet.de.

On the Web

The Tiempo Climate Cyberlibrary provides a listing of

websites on

gender and climate change.

Bright Ideas

General Electric plans to cut solar installation costs by half

Project 90 by 2030 supports South African school children and managers reduce their carbon footprint through its Club programme

Bath & North East Somerset Council in the United Kingdom has installed smart LED carriageway lighting that automatically adjusts to light and traffic levels

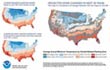

The United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and the American Public Gardens Association are mounting an educational exhibit at Longwood Gardens showing the link between temperature and planting zones

The energy-efficient Crowne Plaza Copenhagen Towers hotel is powered by renewable and sustainable sources, including integrated solar photovoltaics and guest-powered bicycles

El Hierro, one of the Canary Islands, plans to generate 80 per cent of its energy from renewable sources

The green roof on the Remarkables Primary School in New Zealand reduces stormwater runoff, provides insulation and doubles as an outdoor classroom

The Weather Info for All project aims to roll out up to five thousand automatic weather observation stations throughout Africa

SolSource turns its own waste heat into electricity or stores it in thermal fabrics, harnessing the sun's energy for cooking and electricity for low-income families

The Wave House uses vegetation for its architectural and environmental qualities, and especially in terms of thermal insulation

The Mbale compost-processing plant in Uganda produces cheaper fertilizer and reduces greenhouse gas emissions

At Casa Grande, Frito-Lay has reduced energy consumption by nearly a fifth since 2006 by, amongst other things, installing a heat recovery system to preheat cooking oil

Updated: May 15th 2015