Tiempo Climate Cyberlibrary

Priorities for the Poorest

- Tiempo archive

- Complete issues

- Selected articles

- Cartoons

- Climate treaty

- Latest news

- Secretariat

- National reports

- IPCC

About the Cyberlibrary

The Tiempo Climate Cyberlibrary was developed by Mick Kelly and Sarah Granich on behalf of the Stockholm Environment Institute and the International Institute for Environment and Development, with sponsorship from the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency.

While every effort is made to ensure that information on this site, and on other sites that are referenced here, is accurate, no liability for loss or damage resulting from use of this information can be accepted.

|

Nasimul Haque explains the needs and concerns of poor and vulnerable people who are already experiencing the impacts of climate change. The author works with the Know Risk No Risk Campaign, based in the Sustainable Development Resource Centre, Dhaka, Bangladesh. |

Today, over 1.7 billion people are living in conditions of poverty, deprivation and oppression. Per capita emissions of the poorest and most vulnerable population are amongst the lowest. Yet it is the already poor and vulnerable likely to be most affected by the adverse impacts of climate change. Over the past few decades, efforts to reduce poverty through economic growth and redistribution have failed, pushing millions of families beyond limits, into the vicious cycle of poverty. The prevailing will, means and ways to address the interests of the poor in the climate negotiations are governed by a culture and mindset that draws on policies, institutions and processes that so far has resulted in more people becoming poor. The time has come to change this, collectively.

This article explains what priority actions are needed to build the resilience of the poorest and most vulnerable. It advocates a fundamental shift in our collective mindset to enable the most vulnerable to face current and future challenges using their own approaches. It explains the expectations that vulnerable people have from national and international actors and institutions to help them in their struggle for resilience. Priority actions are proposed to national and international policy makers for consideration and action.

Enabling the poor and vulnerable to access resources and services to address climate change related impacts and risks is their right. They do not want charity but rather what is owed to them, as enshrined in the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC).

Parties should make provisions for adequate resource commitments, as well as access to full-cost funding for the most poor, to enable them reduce vulnerability to climate change by building on their own resilience.

An overwhelming majority of the poorest and most vulnerable are women, the physically and intellectually challenged, children, and old people. This make the case stronger to give specific attention to build women's capacity by taking necessary steps locally, nationally and internationally. A significant part of adaptation and vulnerability reduction can be achieved by empowering women with rights, security, and access to adequate resources including capacity enhancement based on their expressed needs. International, national, local level planning processes and development programmes must make provisions to integrate gender specific issues and concerns where women from the poorest and most vulnerable groups represent and voice their contexts and concerns and actively engage in addressing them.

Priority adaptation needs including research, capacity building, technology transfer and development, as well as adaptation on the ground must be led by the vulnerable and poor, locally governed and needs-driven. Local governments, development non-governmental organizations, local businesses and financial services are the frontline agencies with established mechanisms to service and respond to the needs of the poor to become resilient.

|

Priority one: commitments to mitigation Establish a mitigation regime with larger greenhouse gas emission reduction targets to reduce the adverse impacts of climate change on future generations. Binding commitments from developed country parties to the UNFCCC are needed to combat the adverse impacts of climate change currently experienced by the poor and vulnerable. |

|

Priority two: information access The poorest and most vulnerable communities have the right to access information early. Real adaptation will occur when they can secure access to the resources and services they need in a timely and adequate manner. This includes access to the right information to help them make decisions thereby building their resilience in the most cost effective way. |

|

Priority three: effective participation To make good decisions on how to build resilience and take adaptation measures, the poor must participate meaningfully and effectively in all decision making that addresses vulnerability reduction and adaptation needs. |

|

Priority four: meeting resource needs Reducing vulnerability to climate change impacts on the ground can be achieved once the appropriate mechanisms, instruments and arrangements are in place to enable the most vulnerable to match their needs and response strategies with their resources. The Global Environment Facility should accept and prioritize local mechanisms to help the most vulnerable access the resources and capacity building they need. |

|

Priority five: supporting bottom-up approaches Parties to the UNFCCC must recognize and support bottom-up approaches to taking meaningful and effective action on adaptation. This process should start with vulnerable people recognizing the climate risks relevant to their survival and livelihood security. Prevailing ‘project’ and ‘study’ based approaches must be replaced with approaches that support spontaneous participation and decision-making by the poor and vulnerable. |

Relevant agencies, stakeholder groups and the vulnerable themselves must engage in mainstreaming climate change concerns and responses into respective planning and development consideration, to initiate and continue vulnerability reduction and adaptation practices holistically over generations. Research and academic institutions, media, pressure groups and all relevant organizations, locally, nationally and globally, should facilitate such processes with appropriate guidance and build their knowledge on why people are poor and how the poor and vulnerable participate in securing their lives, rights and livelihoods through their adaptation practices.

Funds and resources for the most poor and vulnerable to match their adaptation needs and priorities is one issue receiving little real attention. Some actors still contemplate such funds to be made available based on humanitarian considerations. The whole issue of adaptation and funding to facilitate those who are vulnerable and at risk should be centered on the principle of rights and security of poor and vulnerable population, wherever they are.

Pro-poor adaptation requires pro-poor governance. The Parties to the climate treaty must be accountable, transparent and responsible in their actions toward reducing the vulnerability of the poor in general and from climate impacts in particular.

Parties must recognize the difference between accommodation, adjustment and adaptation. The external support a vulnerable family or community can receive is at best contributing to their adaptation process, not making it happen.

Recognition is emerging of the need to include adaptation in their climate change agenda. But it remains unclear what will be considered adaptation to climate change. Vital questions remain unattended: Who should bear the cost? Who shares the cost? Some talk of "differential" adaptation, seeking ways to quantify the potential or actual damage from climate change. Soon we may witness debates on "attribution" and "additionality" in adaptation discourses. What matters most of all, though, is to enable responses the vulnerable communities and people can take to confront climate challenges and to determine how policies, institutions and mechanisms can evolve to enable resilience building.

The immediate challenge is to facilitate understanding on adaptation issues and concerns globally, nationally and most fundamental of all, at the local level, among those poor and vulnerable.

Acknowledgement

This article is based on a Policy Brief by the author

prepared for the Eleventh Conference of the Parties to the

Climate Convention and First Meeting of the Parties to the

Kyoto Protocol Montreal, Canada, November 28th - December

9th 2005.

Further information

Nasimul Haque, Know Risk No Risk Campaign Secretariat,

Sustainable Development Resource Centre, House 11, Road 4,

Dhanmondi, Dhaka 1205, Bangladesh. Email: sdrc@cgscomm.net.

Bright Ideas

General Electric plans to cut solar installation costs by half

Project 90 by 2030 supports South African school children and managers reduce their carbon footprint through its Club programme

Bath & North East Somerset Council in the United Kingdom has installed smart LED carriageway lighting that automatically adjusts to light and traffic levels

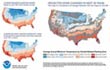

The United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and the American Public Gardens Association are mounting an educational exhibit at Longwood Gardens showing the link between temperature and planting zones

The energy-efficient Crowne Plaza Copenhagen Towers hotel is powered by renewable and sustainable sources, including integrated solar photovoltaics and guest-powered bicycles

El Hierro, one of the Canary Islands, plans to generate 80 per cent of its energy from renewable sources

The green roof on the Remarkables Primary School in New Zealand reduces stormwater runoff, provides insulation and doubles as an outdoor classroom

The Weather Info for All project aims to roll out up to five thousand automatic weather observation stations throughout Africa

SolSource turns its own waste heat into electricity or stores it in thermal fabrics, harnessing the sun's energy for cooking and electricity for low-income families

The Wave House uses vegetation for its architectural and environmental qualities, and especially in terms of thermal insulation

The Mbale compost-processing plant in Uganda produces cheaper fertilizer and reduces greenhouse gas emissions

At Casa Grande, Frito-Lay has reduced energy consumption by nearly a fifth since 2006 by, amongst other things, installing a heat recovery system to preheat cooking oil

Updated: May 15th 2015