Tiempo Climate Cyberlibrary

National Adaptation Programmes of Action: Lessons Learnt in Africa

- Tiempo archive

- Complete issues

- Selected articles

- Cartoons

- Climate treaty

- Latest news

- Secretariat

- National reports

- IPCC

About the Cyberlibrary

The Tiempo Climate Cyberlibrary was developed by Mick Kelly and Sarah Granich on behalf of the Stockholm Environment Institute and the International Institute for Environment and Development, with sponsorship from the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency.

While every effort is made to ensure that information on this site, and on other sites that are referenced here, is accurate, no liability for loss or damage resulting from use of this information can be accepted.

|

|

Balgis Osman-Elasha and Thomas Downing define the lessons learned from preparing National Adaptation Programmes of Action in eastern and southern Africa. |

| Balgis Osman-Elasha is a senior researcher at the Climate Change Unit in the Higher Council for Environment and Natural Resources, Khartoum, Sudan. Thomas Downing is director of the Stockholm Environment Institute, Oxford, United Kingdom. | ||

This article considers the lessons learnt by National Adaptation Programme of Action (NAPA) teams in eastern and southern Africa. It assesses what has been learnt from this international effort to identify urgent adaptation needs and begin implementing priority climate adaptation projects. Evidence is drawn from discussions with NAPA experts and teams, and focuses mainly on strengths and weaknesses of the NAPA process and constraints on achieving NAPA objectives. The article also identifies current opportunities and future prospects for implementing the NAPA recommendations.

During the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change Lead Authors meeting for Working Group II, held in Cape Town in September 2006, a dialogue was held with participants from Botswana, the United Kingdom, Germany, Kenya, Mexico, the Netherlands, South Africa and Sudan. Responding to questions on the main strengths of the NAPA process, there was general agreement about the important role the process played in creating a wider awareness and a sense of ownership amongst various stakeholder groups at different levels, from policy-makers down to the general public at the village level. This was largely attributed to the following NAPA characteristics, described in the order identified by the NAPA teams:

- emphasis on participatory processes;

- consideration of both vulnerability and adaptation to climate change;

- investigation of climate variability as well as climate change;

- a bottom-up approach; and,

- capacity building and awareness raising.

The NAPA teams agreed that the steps leading to the formulation of the NAPA worked well, particularly in terms of identifying stakeholders, focusing on the most vulnerable groups in different sectors or regions, involving planners and policy-makers and providing platforms for discussion and consultation. The data collection process has also been successful, and the employment of a variety of methods to formulate the NAPAs was identified as a key success factor. These methods included literature surveys of previous studies and assessments, direct interviews and meetings, and the use of Global Information Systems, remote sensing technology and other forms of data analysis.

The use of national workshops ensured the involvement of a wide range of stakeholders across the country, particularly policy-makers, funding agencies and international organizations. Second to the national workshops were local-level workshops, which were used as platforms for discussion and exchange of ideas amongst local stakeholders. They involved local stakeholder groups and were usually organized at the level of the state or locality. These workshops proved to be an effective means of communication and knowledge transfer. They also raised local community awareness about the potential impacts of climate change and the need for adaptation. Thirdly was the use of individual and group interviews with selected key stakeholders. These stakeholders were usually the most influential and knowledgeable people at the community level, for instance, local leaders, teachers, midwives and extension officers.

|

"One of the most important achievements of the NAPA is the awareness created at all levels particularly among local people, as it has enabled us to conduct more than 15 workshops covering five ecological regions in five different states" Ismail Elgizouli, NAPA Coordinator, Sudan |

Institutional barriers were a key constraint to the NAPA process, delaying execution of some of the activities. For instance, bureaucratic structures in some institutions hindered the free exchange of information amongst the different NAPA team members. Other constraints included:

- communication problems between the central offices and states;

- a lack of sufficient local-level technical capacity needed to play an active role in the assessment process; and,

- insufficient financial resources and time, especially for large countries like Sudan and Ethiopia.

|

The NAPA process: weaknesses and constraints |

NAPA priorities reflect country-driven criteria and existing national planning frameworks, as well as a primary focus on climatic risks. Some issues and project types were not included. Adaptation as a right, based on equitable sharing of the global climate change burden, and the notion of an 'adaptation deficit' in developing countries, are not prominent in the NAPA proposals. Broader sustainable development issues are implicit in some respects, for example, where the focus is on poverty reduction and stakeholder engagement. But actions for reducing conflict, implementing institutional and structural reforms and empowering disadvantaged communities are not widely reflected in the NAPAs.

The NAPA teams were in general agreement about the need to maintain the momentum created by the NAPA process. Time is an important component of adaptation activities. The main concern stressed by all NAPA teams was the vital and urgent need to secure funding for the implementation phase.

|

Democratic Republic of the Congo

© François Goemans/EC/ECHO |

One potential constraint is the need by most countries for additional technical and financial assistance to develop the concept notes and project profiles into full projects. Another concern expressed by the NAPA teams relates to how best to ensure that NAPA projects get mainstreamed into national development plans and strategies.

|

"The NAPA is about taking immediate actions to address urgent needs - we don’t need to waste more time in improving the document and should present those country-driven projects for funding as soon as possible" Boni Biagini, Senior Climate Change Specialist, Programme Manager, Global Environment Facility |

The consultation and continuous dialogue between scientists and other stakeholders proved to be an efficient way to raise awareness and build capacity amongst a wide range of stakeholders. Adaptation actions need to be taken at all levels (vertically and horizontally) and should provide room to involve all relevant stakeholders. Africa possesses a wealth of local knowledge relevant to adaptation that could significantly contribute to reducing vulnerability if properly utilized. Any planning for adaptation must be firmly rooted in this development knowledge in terms of what works, and where and when it works. Approaching climate change adaptation as a discrete planning process, segmented into a variety of activities, is likely to be less effective than building a broad understanding of the issue and taking action involving multiple stakeholders. Learning by doing, social learning, community-based adaptation and participatory assessment are relevant frameworks in which to take this forward.

|

"It is important not to raise too much expectation from the NAPA and to view it as one ring in a chain of measures that are required and should be implemented in order to achieve real adaptation" Isabelle Niang Diop, Lecturer, University of Dakar, Senegal |

Our most important conclusion is that the NAPAs, as a process, should not be viewed solely as end products in themselves. In many countries (but perhaps not all as yet), the NAPAs have been effective in raising awareness at least amongst national stakeholders. They have also put climate change adaptation on the development agenda. The NAPAs should be seen as an essential step in developing the adaptation capacity of Least Developed Countries (LDCs). Moreover, NAPAs have provided the means and tools required by the LDCs to present and negotiate country-driven action programmes.

We believe there is ample justification for continuing the NAPA processes in LDCs, as ongoing exercises to develop climate adaptation actions, strategies and policies. The form and administration of each NAPA may, however, need adjusting. This is an issue for further research.

Acknowledgement

This article is based on a report commissioned by the European Capacity Building Initiative. Permission to reproduce material from that report is gratefully acknowledged. The original report is available for download.

Further information

Balgis Osman-Elasha, Climate Change Unit in the Higher Council for Environment and Natural Resources, PO Box 10488, Khartoum, Sudan. Fax: +249-183-787617. Email: balgis@yahoo.com .

Thomas E Downing, SEI-Oxford, Suite 193, 266 Banbury Rd, Oxford, OX2 7DL, United Kingdom. Fax: +44-1865-421898 Email: tom.downing@sei.se. Web: www.sei.se/index.php?page=oxford.

On the Web

The national NAPAs submitted to date are available for download.

Bright Ideas

General Electric plans to cut solar installation costs by half

Project 90 by 2030 supports South African school children and managers reduce their carbon footprint through its Club programme

Bath & North East Somerset Council in the United Kingdom has installed smart LED carriageway lighting that automatically adjusts to light and traffic levels

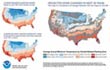

The United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and the American Public Gardens Association are mounting an educational exhibit at Longwood Gardens showing the link between temperature and planting zones

The energy-efficient Crowne Plaza Copenhagen Towers hotel is powered by renewable and sustainable sources, including integrated solar photovoltaics and guest-powered bicycles

El Hierro, one of the Canary Islands, plans to generate 80 per cent of its energy from renewable sources

The green roof on the Remarkables Primary School in New Zealand reduces stormwater runoff, provides insulation and doubles as an outdoor classroom

The Weather Info for All project aims to roll out up to five thousand automatic weather observation stations throughout Africa

SolSource turns its own waste heat into electricity or stores it in thermal fabrics, harnessing the sun's energy for cooking and electricity for low-income families

The Wave House uses vegetation for its architectural and environmental qualities, and especially in terms of thermal insulation

The Mbale compost-processing plant in Uganda produces cheaper fertilizer and reduces greenhouse gas emissions

At Casa Grande, Frito-Lay has reduced energy consumption by nearly a fifth since 2006 by, amongst other things, installing a heat recovery system to preheat cooking oil

Updated: May 15th 2015