Tiempo Climate Cyberlibrary

Seeing REDD in the Amazon

- Tiempo archive

- Complete issues

- Selected articles

- Cartoons

- Climate treaty

- Latest news

- Secretariat

- National reports

- IPCC

About the Cyberlibrary

The Tiempo Climate Cyberlibrary was developed by Mick Kelly and Sarah Granich on behalf of the Stockholm Environment Institute and the International Institute for Environment and Development, with sponsorship from the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency.

While every effort is made to ensure that information on this site, and on other sites that are referenced here, is accurate, no liability for loss or damage resulting from use of this information can be accepted.

|

Virgilio Viana argues that REDD in the Amazon is a win for people, trees and climate. |

| The author is director-general of the Amazonas Sustainable Foundation and a visiting fellow with the International Institute for Environment and Development in London in the United Kingdom. | |

Deforestation remains an entrenched and ongoing issue in the Amazon, the world’s largest and naturally richest rainforest. But Amazonas, Brazil’s largest state, is seeing significant signs of change.

Amazonas harbours some 1.57 million square kilometres of rainforest - six times the size of the United Kingdom. It is also the site of the Juma Sustainable Development Reserve Project, the Amazon’s first independently-validated project where locals are being rewarded for protecting their forests and reducing carbon emissions in the process.

Dubbed REDD for "reduced emissions from deforestation and degradation", such projects are up against a formidable status quo in the Amazon. Deforestation there has an economic and social logic. It is the result of a perverse system that financially rewards those who clearfell, from land grabbers and illegal loggers to agribusiness. Cattle farming, for instance, is a highly profitable enterprise. From 1996 to 2006, numbers of cattle in the Brazilian Legal Amazon - that part of Brazil within the Amazon basin - rose from 37 million to 73 million. Deforestation is not a result of irrationality, ignorance or stupidity: people do get, or expect to get, real benefits from deforestation and unsustainable forest harvesting.

Besides the environmental impacts of expanding agribusiness and poor forestry practices, unsustainable development in the Amazon has also led to significant poverty and social inequality, notably the highest concentration of slavery cases in Brazil. Similar social injustices, targeting indigenous and traditional people in particular, occur on other deforestation fronts throughout the tropics.

Over the past few decades, a cautious optimism has emerged as isolated attempts to curb deforestation have yielded positive results. In Amazonas, deforestation has been in continuous decline, from 1582 square kilometres in 2003 to 479 in 2008 - a 70 per cent decrease. As a result of political change in 2003 with the election of Governor Eduardo Braga, the state enacted a set of public policies aimed at reducing deforestation and improving livelihoods of forest dwellers. Lessons learned there and elsewhere can be expanded, adapted and replicated.

Obviously, the solution is not a simple, technical one. The starting point is no less than a radical change in the development paradigm.

Forests have historically been seen as valueless and forestry as backwards - neither of them worthy of inclusion in "development" strategies or in the usual set of policy instruments encouraging relevant investment, such as tax incentives and credit. Yet the significant problems deforestation causes now suggest that forests need to be regarded as valuable assets to individuals, families, businesses and governments. In short, public, non-profit and private sector policies have to be guided by a simple message: "forests are worth more standing than cut". This paradigm shift has to be translated into broad cross-sectoral policies in areas such as finance, education, health, energy and sustainable land use systems.

Some valuations of standing forests in the Amazon have produced very positive results. On the one hand are the results of public policies aiming to increase the value of forest products - such as honey and managed timber - supporting private sector investment and social-environmental entrepreneurship. In Amazonas, the price paid to producers of andiroba oil, derived from the nut of the Carapa guiansensis tree, increased 3.6 times from 2003 (when sustainable development policies began to be rolled out) to 2008. The more profitable sustainably harvested forest products become, the less attractive deforestation is, and the greater the economic stimulus to conserve forests. On the other hand, environmental services such as carbon sequestration and storage have big potential and are a key part of the equation too. The more valuable environmental services are, the more resources will be available for investment in improving local people’s quality of life and ability to generate income.

| Reducing Emissions from Deforestation in Developing Countries |

|---|

|

"Reducing emissions from deforestation in developing countries and approaches to stimulate action" - REDD for short - entered the agenda of the Conference of Parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change at the eleventh session in Montreal, Canada, in 2005. Reducing deforestation and preventing the release of carbon was recognized as the mitigation option with the largest and most immediate global impact on carbon stock per hectare and per year in the short term. Subsequently, Decision 2/CP.13 provided a mandate for action to reduce emissions from deforestation and forest degradation in developing countries. The main commitments are:

The decision also provided indicative guidance for the implementation and evaluation of demonstration activities. The Good Practice Guidance for Land Use, Land-use Change and Forestry from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change is recommended for estimating and reporting of emissions and removals. Over 2008 and 2009, policy approaches and positive incentives relating to reducing emissions from deforestation and forest degradation in developing countries and, under REDD-plus, the role of conservation, sustainable management of forests and enhancement of forest carbon stocks in developing countries have been considered under the United Nations Framework on Climate Change Secretariat |

The biggest challenge is not how to reduce deforestation, but how to finance the reduction. The agricultural frontier in the Amazon is pushed along by a multi-billion dollar per year economy. If the nature of the battle is predominantly economic, irreversible success will come only with sustainable finance - public, private and non-profit programmes aimed at stopping deforestation for carbon stored, biodiversity conserved, water supply protected or poverty eradicated. Financing a new development paradigm in the Amazon is relatively low in cost compared to the environmental services produced by its standing forest ecosystems.

REDD has opened up the possibility of valuing carbon-based environmental services in the Amazon. Sceptics say there may be methodological problems with REDD, but Amazonas’s groundbreaking Juma project, spearheaded by the Amazonas Sustainable Foundation (FAS), overcame all such barriers, including the establishment of baselines - benchmarks for calculating emissions reduction. In 2008, the scheme was validated according to standards of the Climate, Community & Biodiversity Alliance by the international verification service TÜV SÜD. It passed the methodology test with flying colours.

The goals of the Juma Sustainable Development Reserve Project are:

- to avoid the degradation of 366,151 hectares of rainforest and the emission of 210,885,604 million tones of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere by 2050;

- to generate carbon credit out of 189,767,027 tons of avoided carbon dioxide emissions;

- to halt deforestation in a forest area that is under severe land conversion pressure; and,

- to improve the well-being of forest peoples living in the Juma Sustainable Development Reserve and its surroundings.

Communities in the reserve will be rewarded for their stewardship. Amazonas State will invest resources generated by avoided carbon emissions in controlling and monitoring deforestation within the Juma reserve and improving the region’s living standards. Investments are also expected to generate sustainable economic activities and to sponsor a research and conservation project in and out the Juma reserve.

| Bolsa Floresta |

|---|

|

The Juma Sustainable Development Reserve Project is part of a broader initiative focused on payments for environmental services: the Bolsa Floresta (forest conservation grant) programme. Initiated by the Amazonas government and Brazilian private banking giant Bradesco, this is now funded by a range of players. The Marriott hotel chain, for instance, is financing Juma through voluntary contributions from guests. The total investment of US$8.1 million per year supports 6000 families committed to zero deforestation in all Bolsa Floresta projects. Families receive direct cash payments through a highly efficient instrument: an electronic debit card accessible in banks and post offices in any town. Communities also receive investments for income generation activities, social programmes and supporting local associations. Poverty eradication is a key component of environmental conservation. Bolsa Floresta is now ready to be scaled up, and the International Institute for Environment and Development is assessing a wide variety of schemes for their potential. |

What is needed to ensure the benefits of REDD? REDD financing mechanisms should be flexible so they can incorporate both inter-governmental funding (at national scale) and market-based funding (at project level). REDD should be allowed in the carbon credit market with a quota to avoid flooding the market. Even a small quota of 10 per cent would generate more resources than any other international financing mechanism for tropical forest conservation and poverty. REDD could tip the financial and governance balance in favour of sustainable forest management. Finally, REDD funding should use instruments such as certification and validation to ensure appropriate benefit sharing for indigenous peoples and local communities.

The global carbon market reached US$118 billion in 2008, but very little of it was invested in protecting tropical rainforests. Meanwhile, the international community faces a process of great strategic importance: the new international climate agreements, to be agreed in December 2009 in Copenhagen. If these include forest carbon as both a market instrument and a mechanism for intergovernmental funding, they will set a historic precedent.

Forest conservation and greenhouse gas emission reduction targets must top the list of priorities in the new climate agreements. REDD can become a significant catalyst of change to stop deforestation and eradicate poverty in many regions of the planet. As Nelson Mandela has said, "Those who are hungry are in a hurry." We urgently need to start a revolution in the world’s forests. Time is running short.

Acknowledgements

This article is derived, with permission, from an opinion paper published by the International Institute for Environment and Development. The opinion paper was produced with support from the Danish International Development Agency, the United Kingdom Department for International Development, the Dutch Directorate-General for International Cooperation, Irish Aid, Norwegian Agency for Development Co-operation, Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation and Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency.

Further information

Virgilio Viana, International Institute for Environment and Development, 3 Endsleigh Street, London WC1H 0DD, United Kingdom. Fax: +44-20-73882826. Email: virgilio.viana@fas-amazonas.org. Web: www.iied.org and www.fas-amazonas.org/en.

On the Web

A video interview with Virgilio Viana is available. Details of the methodology developed to quantify reduction emissions from deforestation can be downloaded. The REDD Web Platform provides access to information and resources on reducing emissions from deforestation in developing countries.

Bright Ideas

General Electric plans to cut solar installation costs by half

Project 90 by 2030 supports South African school children and managers reduce their carbon footprint through its Club programme

Bath & North East Somerset Council in the United Kingdom has installed smart LED carriageway lighting that automatically adjusts to light and traffic levels

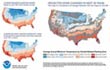

The United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and the American Public Gardens Association are mounting an educational exhibit at Longwood Gardens showing the link between temperature and planting zones

The energy-efficient Crowne Plaza Copenhagen Towers hotel is powered by renewable and sustainable sources, including integrated solar photovoltaics and guest-powered bicycles

El Hierro, one of the Canary Islands, plans to generate 80 per cent of its energy from renewable sources

The green roof on the Remarkables Primary School in New Zealand reduces stormwater runoff, provides insulation and doubles as an outdoor classroom

The Weather Info for All project aims to roll out up to five thousand automatic weather observation stations throughout Africa

SolSource turns its own waste heat into electricity or stores it in thermal fabrics, harnessing the sun's energy for cooking and electricity for low-income families

The Wave House uses vegetation for its architectural and environmental qualities, and especially in terms of thermal insulation

The Mbale compost-processing plant in Uganda produces cheaper fertilizer and reduces greenhouse gas emissions

At Casa Grande, Frito-Lay has reduced energy consumption by nearly a fifth since 2006 by, amongst other things, installing a heat recovery system to preheat cooking oil

Updated: May 15th 2015