Tiempo Climate Cyberlibrary

Sustainable Village Energy in Lao PDR

- Tiempo archive

- Complete issues

- Selected articles

- Cartoons

- Climate treaty

- Latest news

- Secretariat

- National reports

- IPCC

About the Cyberlibrary

The Tiempo Climate Cyberlibrary was developed by Mick Kelly and Sarah Granich on behalf of the Stockholm Environment Institute and the International Institute for Environment and Development, with sponsorship from the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency.

While every effort is made to ensure that information on this site, and on other sites that are referenced here, is accurate, no liability for loss or damage resulting from use of this information can be accepted.

|

Adam Harvey describes a successful programme designed to provide sustainable forms of energy to villages in Lao PDR. The author is Adviser to the Off-Grid Programme of the Ministry of Industry and Handicraft in Vientiane, Lao PDR. |

In Lao PDR, ad hoc solutions to rural electricity supply exist everywhere on a household-by-household basis. Small private hydro generators powered by local irrigation channels and rivers may be used or an entrepreneur may charge batteries or connect wires from a private diesel generator to several houses.

These kinds of solutions are generally expensive, unsafe, unreliable or available only seasonally. Expenditure by villagers is often in the order of US$2 per month or more. Poorer households relying on non-electrical lighting from wick-lamps, typically spend more than US$1 per month on fuel, and receive a very inadequate standard of illumination.

Improved lighting in rural houses is generally considered a major step forward in the quality of life. It stimulates better health practice (use of mosquito nets, hygiene), increased opportunities for education, and evening income-generating activities. The use of radios and televisions is often considered a step forward in terms of increased knowledge and motivation. Daytime electricity supply gives rise to a greater range of income-generating opportunities.

Reliable and better-quality electricity services are in strong demand from rural people.

Over the past three years, a team of Lao experts has been training small companies to become village energy service specialists, to work in areas not due for electricity grid connection. These Electricity Service Companies offer a choice of electricity supply technology, so that there is a solution for each village.

Most villages have chosen Solar Home Systems, but as the companies begin to work in the remoter cloudy and hilly areas, more villagers are choosing village-scale hydro systems.

This article outlines progress with the off-grid programme so far, focusing on 'best practices', that is, choices we have made through careful testing of options, to ensure reliable service for Lao villagers and a self-sustaining framework for implementing companies. We have tried to move from project-cycle vulnerability, to a solid national programme providing real opportunity for the private sector and for the majority of Lao villagers.

The off-grid programme

A major challenge for the programme has been to develop a framework within which an increasing number of companies can operate consistently over many years into the future.

An ambitious goal for Laos is to connect 75 per cent of rural families to the grid by 2020, and to help at least another 15 per cent to receive off-grid electricity by this time. This would mean companies could be delivering over 10,000 connections per year over the next fifteen years as well as providing ongoing service support to large numbers of operational systems.

|

|

So far, we have worked mostly in provinces which have plenty of sunshine, where the most popular choice has been the Solar Home System. There are several sizes available at different prices. Up to now about half the subscribers have chosen 20W panels, and about one third have chosen 50W panels © Adam Harvey |

Another key challenge has been to make sure the stand-alone electricity installations operate reliably for many years.

The solution has been to develop a 'rent-to-buy' or hire-purchase mechanism. In the case of villagers choosing Solar Home Systems, they buy the equipment by monthly payments over a period of several years. The solar panel then becomes an important economic asset to poor families, since it retains high re-sale value. The villagers choose a Village Electricity Manager to provide technical support over this period and beyond.

In the case of hydro and engine-generators, this Village Electricity Manager hire-purchases the equipment personally, using it to run a small business selling electricity. In both cases, prospective ownership has proved in practice to be an excellent motivation to take care of the equipment.

The Village Electricity Manager and the Electricity Service Company both receive a portion of each monthly hire-purchase payment. In this way, a technical and management structure is permanently in place to support the long-term needs of operational customers. Both the Company and the Village Electricity Manager have a strong incentive to maintain the equipment in good working order, as they lose income if villagers withhold payments for any reason.

|

Background information The off-grid programme has been developed by an Off-Grid Promotion and Support Office located within the Ministry of Industry and Handicraft in Vientiane. The team includes government officials, and personnel recruited from the private sector. The work is funded by a soft loan from the World Bank, combined with a Global Environment Facility grant. The programme started in 1999 with pilot work in villages on low-cost technology, local manufacture and participative and business-orientated planning procedures, then progressed through 2000 and 2001 to the creation of appropriate government policies and regulations. By 2002 a professional consulting team was in place, and companies started to be trained. In 2003 the bulk of the dissemination work was carried out by the Electricity Service Companies. The programme is to be extended in the period 2005 to 2010 to connect about 30,000 more households. During this five-year period a structure (an Off-Grid Promotion or Rural Energy Fund) will be established to attract additional soft credit from sources other than the World Bank, in order that the rate of dissemination can approach that required (an average of 10,000 a year) for achievement of the Lao government goal of 90 per cent electrification by improved systems by 2020. |

Although the focus of the programme so far has been on electricity supply, the regulatory framework and financing approach has been designed to work for a wide range of renewable energy options for rural communities.

The Electricity Service Companies are able to diversify into technologies such as biogas-based cooking, biomass or solar thermal powered generators, using the same financing and administration structure. This financing method is suitable for energy installations orientated toward production and processing as well as for domestic needs, and the programme is starting to prioritize productive applications.

Reliability

Our delivery system is designed for reliability. The main mechanism is financial incentive. This works in three ways.

First, the Solar Home System user is buying the equipment, and is motivated to take care of it so as not to lose their investment. In the case of village electricity distribution systems (village hydro, generator-sets, windpower, solar inverters, and so on), the Village Electricity Manager makes a significant private investment and looks forward to increased income at the end of the hire-purchase period. This person is, therefore, motivated to keep the equipment in good condition. They depend on tariff payments for their livelihood, and so are interested and motivated in providing a reliable supply every night.

|

|

© Adam Harvey |

|

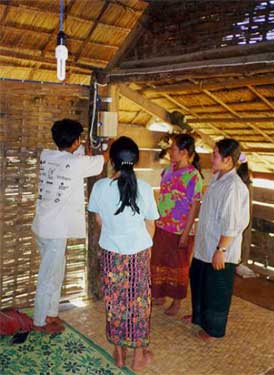

Village hydro systems are operated and purchased over five years by Village Electricity Managers. The systems have many improved features, such as a current limiter in each house, regulated voltage and automatic safety trips. These features ensure that management is feasible and that customers receive reliable and safe supply. The same features and financing arrangements apply to engine-generator systems, which will be powered by locally-grown bio-fuels. One element of the participative planning process undertaken in each village is selection of the Village Electricity Manager |

|

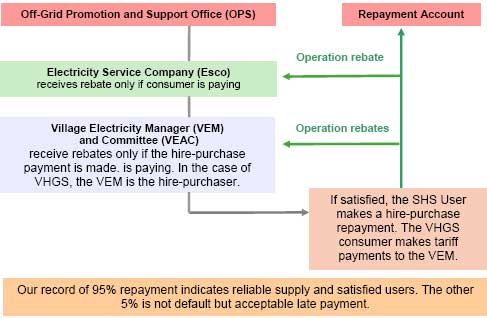

The second financial incentive works through the Village Electricity Manager, the Village Electricity Advisory Committee (a mediating body) and the Electricity Service Companies all receiving a portion of each user's payment. These portions are called "operational rebates" (see Figure 1).

The operational rebates are received only if the user payment is actually made. An unreliable system means the customer does not pay, so the Manager, the Committee, and the Company all lose their rebate. They are, therefore, motivated to think ahead, keep spare parts in stock, check for early warning signs of faults, and make sure the customer knows how to use the equipment well and avoid problems. They become expert at preventive maintenance. They want their customers to be satisfied.

Through the third financial incentive, the Off-Grid Promotion and Support Office does not approve plans for installations in new villages if the Electricity Service Company is not maintaining an average repayment rate above 95 per cent from all their villages. If the Company allows reliability to slip, repayments will slip and the business will fail. The Company is in competition with other Electricity Service Companies, who would then expand their business in their area.

The Off-Grid Promotion and Support Office has designed the Electricity Service Company licence agreement to open each area up to competition two years from the date of signing.

Another method of ensuring reliability is the progressive increase in private investment by Village Electricity Managers and Electricity Service Companies. This is recouped through reliable payments by customers over many years.

|

|

|

Figure 1: The financing system is common to all technologies and is based on performance incentives which prompt the Village Electricity Manager and the Village Electricity Advisory Committee to think ahead, care for their consumers, carry out preventive maintenance and stock spare parts, so underpinning long-term reliability |

If repayment performance is good, reliability is good. Our delivery system has a repayment performance from consumers of over 95 per cent. The shortfall is considered the result of acceptable late payments rather than defaults. As of December 2004, 5,000 villagers are receiving "every night, light", the motto adopted by some of the Electricity Service Companies, some already for four years.

Sustainability

We have designed the delivery mechanism to be robust, by building in financial incentives and ownership incentive to achieve reliable performance. Nevertheless, the steering of this mechanism remains a challenge for forthcoming years.

Although one aspect of sustainability is full commercialization, it is unrealistic to expect that most rural families can afford off-grid under fully commercial conditions. Wealthy villagers, possibly only 10 per cent of the rural population, would be the sole beneficiaries leaving the majority worse off.

Sufficient soft loan funding for 200,000 off-grid connections will hopefully be available in forthcoming years in Laos (the World Bank is now considering a credit to expand this programme to reach 30,000 households). In the context of this credit, our programme makes sure that villagers experience commercial conditions, interacting with private companies on the basis of clear price lists and payment terms.

|

|

|

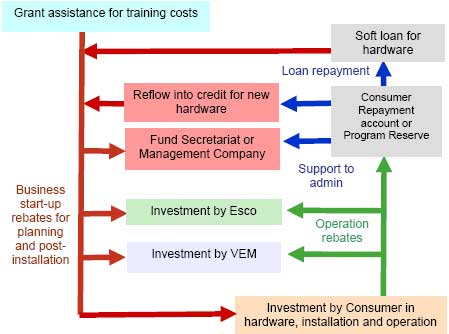

Figure 2: Contributions to investment and operational costs |

Figure 2 shows that operational costs are met by consumer repayments, and as the volume of customers grows, a repayment reserve is accumulated.

Even at the current low connection rate, there is already enough reserve to self-finance the administration of the programme for one year. This means that Laos now has a national programme which can continue to function regardless of fluctuations in external support. It is not dependent on project funding cycles, although its rapid expansion does depend on an inflow of soft loans.

Drawing from the reserve, customers with off-grid connections continue to receive back-up support from Village Electricity Managers and Electricity Service Companies, who themselves receive back-up from the Off-Grid Promotion and Support Office, even if for a period no external inflow of credit is available for new equipment installations. As the reserve grows larger, it is possible for it to also cover loan repayment costs and to provide credit for new installations.

|

|

Mr Bounthan registered Sengsavan in April 2003 and was awarded Electricity Service Company status in August 2003. He provides operational support services to over 30 Village Electricity Managers and their Solar Home System customers in Vientiane Province © Adam Harvey |

Productive opportunities

Villagers in Laos are quick to use small electricity supply for income generation.

For example, in one village taking Solar Home Systems, most of the houses immediately moved their weaving looms upstairs. The teenagers were very happy to contribute extra income weaving in the evenings. This income paid back the cost of the solar panel and weaving materials after which there was additional money for the family.

In the same village, we were told the solar lights had increased incomes by allowing net mending to take place at night, and also by allowing the charging of batteries used for fishing and for hunting frogs at night.

In one village with hydro supply, the villagers told us the electric light had increased their incomes significantly. Many of the families make small baskets for sale to tourists. Now that extra hours of good quality light are available from the hydro, they are earning significant extra income. With these returns they are more than happy to pay the monthly hydro tariff.

|

|

The Village Electricity Manager introduces consumers to safe use of electricity and explains the purpose of the current limiter © Adam Harvey |

One lady uses the light to sew in the evenings for her customers, one uses a fridge to make cold sweets for sale. A carpenter is using power tools in the daytime, and the Village Electricity Manager is charging batteries for fee-payment. At one stage, ice production started as it proved to be a profitable application.

In conclusion, it would be fair to say that the programme to date has been highly successful which is, in the main, due to the enthusiasm and motivation of the villagers. It is hoped that the plans for further expansion of energy supplies to more villagers will have the same positive outcome.

Further information

Adam Harvey, Off-Grid Promotion and Support Office (OPS),

PO Box 9020, Vientiane, Lao PDR. Tel: +856-20-5615488.

Email: adamharvey@compuserve.com.

On the Web

The Tiempo Climate Cyberlibrary provides a listing of

theme sites on renewable energy.

Acknowledgements

This feature is based on detailed description of the

programme published in “Renewable Energy for

Development” (Vol. 17, No. 2, 2004), the newsletter

of the Energy Programme at the Stockholm Environment

Institute. This article can be obtained from the author or

by contacting the Stockholm Environment Institute, Box

2142, SE-103 14 Stockholm, Sweden. Fax: +46-8-7230348.

Email: postmaster@sei.se. Web:

www.sei.se.

Bright Ideas

General Electric plans to cut solar installation costs by half

Project 90 by 2030 supports South African school children and managers reduce their carbon footprint through its Club programme

Bath & North East Somerset Council in the United Kingdom has installed smart LED carriageway lighting that automatically adjusts to light and traffic levels

The United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and the American Public Gardens Association are mounting an educational exhibit at Longwood Gardens showing the link between temperature and planting zones

The energy-efficient Crowne Plaza Copenhagen Towers hotel is powered by renewable and sustainable sources, including integrated solar photovoltaics and guest-powered bicycles

El Hierro, one of the Canary Islands, plans to generate 80 per cent of its energy from renewable sources

The green roof on the Remarkables Primary School in New Zealand reduces stormwater runoff, provides insulation and doubles as an outdoor classroom

The Weather Info for All project aims to roll out up to five thousand automatic weather observation stations throughout Africa

SolSource turns its own waste heat into electricity or stores it in thermal fabrics, harnessing the sun's energy for cooking and electricity for low-income families

The Wave House uses vegetation for its architectural and environmental qualities, and especially in terms of thermal insulation

The Mbale compost-processing plant in Uganda produces cheaper fertilizer and reduces greenhouse gas emissions

At Casa Grande, Frito-Lay has reduced energy consumption by nearly a fifth since 2006 by, amongst other things, installing a heat recovery system to preheat cooking oil

Updated: May 15th 2015