Tiempo Climate Cyberlibrary

Greenhouse Development Rights

- Tiempo archive

- Complete issues

- Selected articles

- Cartoons

- Climate treaty

- Latest news

- Secretariat

- National reports

- IPCC

About the Cyberlibrary

The Tiempo Climate Cyberlibrary was developed by Mick Kelly and Sarah Granich on behalf of the Stockholm Environment Institute and the International Institute for Environment and Development, with sponsorship from the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency.

While every effort is made to ensure that information on this site, and on other sites that are referenced here, is accurate, no liability for loss or damage resulting from use of this information can be accepted.

|

Sivan Kartha describes an innovative scheme for allocating emissions targets that preserves development priorities. |

| The author is coordinator of the Stockholm Environment Institute’s Climate Program based in Boston in the United States. | |

A worldwide warming of two degrees Celsius over pre-industrial temperatures has been widely endorsed as the maximum that can be tolerated or even managed as climate change develops. Yet even as the emerging science increasingly underscores how extremely dangerous it would be to exceed two degrees, many people are losing all confidence that today’s inertial, politics-bound societies will be able to prevent such a warming. Our quite different conclusion is that the two degrees Celsius line can indeed be held, but that doing so demands a sharp break with politics as usual.

Carbon-based growth is no longer a viable option in either the North or the South, so we set out to assess the problem of rapid decarbonization in a world sharply polarized between North and South and, on both sides, between rich and poor.

|

| Figure 1: The emissions space for developing countries. The blue line shows a two degrees Celsius emergency pathway, in which global carbon emissions peak in 2013 and fall to 80 per cent below 1990 levels in 2050. The dotted line shows Annex I emissions declining to 90 per cent below 1990 levels in 2050. The black line shows, by subtraction, the emissions "space" that would remain for the developing countries. Note that even this extraordinarily ambitious global trajectory presents a 15 to 30 per cent chance of exceeding a two degrees Celsius temperature rise. |

As Figure 1 shows, even if the industrialized nations undertake bold efforts to virtually eliminate their emissions by 2050, the carbon budget that would remain to support the South’s development remains alarmingly small. Developing country emissions would still have to peak only a few years later than those in the North - before 2020 - and then decline by nearly six per cent annually through 2050. This would have to take place while most of the South’s citizens were still struggling in poverty and desperately seeking a significant improvement in their living standards.

It is this last point that makes the climate challenge so daunting. For the only proven routes to development - to water and food security, improved health care and education, and secure livelihoods - involve expanding access to energy services, and, given today’s inadequate, expensive, low-carbon energy systems and the South’s limited ability to afford them, these routes inevitably threaten an increase in fossil-fuel use and thus carbon emissions. From the South’s perspective, this pits development squarely against climate protection.

With even with the minimal Millennium Development Goals being treated as second-order priorities, the developing countries are quite manifestly justified in fearing that the larger development crisis, too, will be treated as secondary to the imperatives of climate stabilization. The level of international trust is very low indeed and, all told, the situation invites global political deadlock. Despite progress at the margins, the climate negotiations are moving far, far too slowly.

It is unlikely that we will be able to act, decisively and on the necessary scale, until we openly face the big question: What kind of a climate regime can allow us to bring global emissions rapidly under control, even while the developing world vastly scales up energy services in its ongoing fight against endemic poverty and for human development?

The development threshold

Development is more than freedom from poverty. The real issue is a path beyond poverty to dignified, sustainable ways of life, and the right to such development must be acknowledged and protected by any climate regime that hopes for even a chance of success. Accordingly, the Greenhouse Development Rights framework (GDRs), which has been developed by the Stockholm Environment Institute and EcoEquity, is designed to protect the right to sustainable human development, even as it drives rapid global emission reductions. It proceeds in the only possible way, by operationalizing the official principles of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), according to which states commit themselves to "protect the climate system... on the basis of equity and in accordance with their common but differentiated responsibilities and respective capabilities."

As a first step, the GDRs framework codifies the right to development as a "development threshold" - a level of welfare below which people are not expected to share the costs of the climate transition. This threshold, please note, is emphatically not an "extreme poverty" line. Rather, it is set to be higher than the global poverty line, to reflect a level of welfare that is beyond basic needs but well short of today’s levels of affluent consumption.

|

|

Traffic in Delhi

© Kevin Hicks/SEI |

People below this threshold are taken as having development as their proper priority. As they struggle for better lives, they are not similarly obligated to labour to keep society as a whole within its sharply limited global carbon budget. People above the threshold, on the other hand, are taken as having realized their right to development and as bearing the responsibility to preserve that right for others. Critically, these obligations are taken to belong to all those above the development threshold, whether they happen to live in the North or in the South.

The level where a development threshold would best be set is clearly a matter for debate. We argue that it should be at least modestly higher than the global poverty line, which is derived from an empirical analysis of the income levels at which the classic plagues of poverty - malnutrition, high infant mortality, low educational attainment, high relative food expenditures - begin to disappear or, at least, become exceptions to the rule. We take a figure 25 per cent above the global poverty line of US$16 a day (purchasing power parity adjusted) for our indicative calculations, which are, therefore, relative to a development threshold of US$20 per person per day (US$7500 per person per year). This income also reflects the level at which the southern "middle class" begins to emerge.

Capacity, responsibility and national obligations

Once a development threshold has been defined, capacity and responsibility can be identified, and these can then be used to calculate the fraction of the global climate burden that should fall to any given country.

Capacity is income not demanded by the necessities of daily life, and thus available to be "taxed" for investment in climate mitigation and adaptation and can be straight-forwardly interpreted as total income excluding income below the development threshold. This is illustrated in Figure 2 below, which shows the development threshold as it crosses the national income distribution lines and splits their populations into a poorer portion (to the left) and a wealthier portion (to the right). This crossing makes it easy to compare both the heights of wealth and the depths of poverty in different countries, and also graphically conveys each country’s capacity (the paler blue area), which we define as the income that the wealthier portion of the population has above the development threshold.

|

| Figure 2: Capacity - income above the development threshold. These curves approximate income distributions within India, China and the United States. The paler blue areas represent national incomes above the US$20 per person per day development threshold. Chart widths are scaled to population, so these capacity areas are correctly sized in relation to each other. Based on projected 2010 data. |

A nation’s aggregate capacity, then, is defined as the sum of all individual income, excluding income below the threshold. Responsibility, by which we mean contribution to the climate problem, is similarly defined as cumulative emissions since 1990, excluding emissions that correspond to consumption below the development threshold. Such emissions, like income below the development threshold, do not contribute to a country’s obligation to act to address the climate problem.

Thus, both capacity and responsibility are defined in a manner that takes explicit account of the unequal distribution of income within countries. This is a critical and long-overdue move, because the usual practice of relying on national per-capita averages fails to capture either the true depth of a country’s developmental need or the actual extent of its wealth. These measures of capacity and responsibility can then be straightforwardly combined into a single indicator of obligation, in a Responsibility Capacity Index (RCI). This calculation is done for all Parties to the UNFCCC, based on country-specific income, income distribution and emissions data.

The precise numerical results depend, of course, on the particular values chosen for key parameters, such as the year in which national emissions begin to count toward responsibility (we use 1990, but a different starting date can certainly be defended) and, especially, the development threshold. The results also evolve over time; the global balance of obligation in 2020, or 2030, can be expected to differ considerably from that which exists today. Beyond that, the values of specific parameters can be easily adjusted and should certainly be debated; all of them, of course, would have to be negotiated.

What’s most important is that the GDRs framework lays out a straightforward operationalization of the United Nations’ official differentiation principles, and that it does so in a way that protects the poor from the burdens of climate mobilization.

Indicative calculations

Our indicative calculations are by no means definitive, but they are instructive. Looking at just the 2010 numbers in the table below, they show that the United States, with its exceptionally large share of the global population of people with incomes above - and generally far above - the US$20-per-day development threshold (capacity), as well as the world’s largest share of cumulative emissions since 1990 (responsibility), is the nation with the largest share (33.1 per cent) of the global RCI. The European Union follows with a 25.7 per cent share; China, despite being relatively poor, is large enough to have a rather significant 5.5 per cent share, which puts it even with the much smaller but much richer country of Germany. India, also large but much poorer, falls far behind China with a mere 0.5 per cent share of the global RCI. These are the shares of the costs of the global programme of both mitigation and adaptation that each country would be obliged to bear.

| 2010 | 2020 | 2030 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population (per cent of global) | GDP per capita ($US PPP) | Capacity (per cent of global) | Responsibility (per cent of global) | RCI (per cent of global) | RCI (per cent of global) | RCI (per cent of global) | |

| EU27 | 7.3 | 30,472 | 28.8 | 22.6 | 25.7 | 22.9 | 19.6 |

| EU15 | 5.8 | 33,754 | 26.1 | 19.8 | 22.9 | 19.9 | 16.7 |

| EU+12 | 1.5 | 17,708 | 2.7 | 2.8 | 2.7 | 3.0 | 3.0 |

| United States | 4.5 | 45,640 | 29.7 | 36.4 | 33.1 | 29.1 | 25.5 |

| Japan | 1.9 | 33,422 | 8.3 | 7.3 | 7.8 | 6.6 | 5.5 |

| Russia | 2.0 | 15,031 | 2.7 | 4.9 | 3.8 | 4.3 | 4.6 |

| China | 19.7 | 5,899 | 5.8 | 5.2 | 5.5 | 10.4 | 15.2 |

| India | 17.2 | 2,818 | 0.7 | 0.3 | 0.5 | 1.2 | 2.3 |

| Brazil | 2.9 | 9,442 | 2.3 | 1.1 | 1.7 | 1.7 | 1.7 |

| South Africa | 0.7 | 10,117 | 0.6 | 1.3 | 1.0 | 1.1 | 1.2 |

| Mexico | 1.6 | 12,408 | 1.8 | 1.4 | 1.6 | 1.5 | 1.5 |

| Least Developed Countries | 11.7 | 1,274 | 0.1 | 0.04 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| Annex I | 18.7 | 30,924 | 75.8 | 78.0 | 77 | 69 | 61 |

| Non-annex I | 81.3 | 5,096 | 24.2 | 22.0 | 23 | 31 | 39 |

| High-income | 15.5 | 36,488 | 76.9 | 77.9 | 77 | 69 | 61 |

| Middle-income | 63.3 | 6,226 | 22.9 | 21.9 | 22 | 30 | 38 |

| Low-income | 21.2 | 1,599 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.5 |

| World | 100 | 9,929 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Notes: Results are based on projected emissions and income for 2010, 2020, and 2030. High-, middle-, and low-income country categories are based on World Bank definitions as of 2006. Projections based on International Energy Agency World Energy Outlook 2007. | |||||||

| Key: EU27 = current membership of the European Union (EU). EU15 = membership of the EU prior to May 2004. EU+12 = new members since May 2004. GDP = Gross Domestic Product. PPP = purchasing power parity adjusted. | |||||||

These results are striking for two reasons. First, they acknowledge the emergence of a consuming class in the developing world, and calculate its capacity and responsibility to be rather significant. Indeed, nearly one-quarter (23 per cent in 2010) of the total global obligation is assigned to developing countries and, looking toward 2030, this portion continues to grow. This is most evident in China’s projected share of the total obligation, which nearly triples over two decades (from 5.5 per cent to 15.3 per cent), reflecting an extremely rapidly growing economy and an increasing number of Chinese people who are projected to enjoy incomes above the development threshold. Once the industrialized countries have fulfilled their obligation to "take the lead" (in the words of the climate treaty), it will be reasonable to expect the developing world to likewise start bearing its burden.

The second - and more dramatic - implication is for the industrialized world, which carries the vast majority of the global obligation and will continue to do so well into the future. It goes without saying that the industrialized world must invest in radically mitigating its own emissions. But, ultimately, it is in the developing world where most mitigation must happen, since this is where most emissions now occur and where emissions are growing most rapidly. (The same may be said of adaptation.)

Thus, the industrialized world, to carry its legitimate share of the climate burden, must fulfill a two-fold obligation:

- it must drive extraordinarily ambitious domestic reductions and thus free up enough environmental space for the poorer countries to develop; and,

- it must drive equally ambitious international efforts - via technological and financial support - to enable this development to occur along a low-emission, high-adaptation path.

Admittedly, this will be seen as a dangerous idea. It plainly illustrates that a climate regime that preserves a right to development - the only kind of climate regime that is politically viable - calls upon industrialized countries to do far more than they have yet signaled a willingness to do. It also suggests that the only possible way to build a consensus in the industrialized countries to honour a right to development and to bear their fair share of the global climate burden is for the consuming classes in the developing world to also bear their fair share. The alternative is a weak regime with little chance of preventing a climate catastrophe.

But it is also a liberating idea. It defines and quantifies national obligations in a way that explicitly safeguards a meaningful right to development. It accepts the developing country negotiators’ claim that they can only accept a regime that protects development and, just as importantly, it tests the willingness of the industrialized countries to step forward and offer such a regime.

Acknowledgements

This article is based on material extracted from the report, The Greenhouse Development Rights Framework, published by the Heinrich Böll Foundation, Christian Aid, EcoEquity and the Stockholm Environment Institute. The author acknowledges the contribution of the co-authors of that report, Paul Baer, Tom Athanasiou and Eric Kemp-Benedict.

Further information

Sivan Kartha, Stockholm Environment Institute, 11 Curtis Avenue, Somerville, MA 02144-1224, USA. Fax: +1-617-4499603. Email: skartha@sei-us.org. Web: www.sei-us.org.

On the Web

You can experiment with the sensitivity of these results, relative to alternative parameterizations, using the online GDRs calculator.

Bright Ideas

General Electric plans to cut solar installation costs by half

Project 90 by 2030 supports South African school children and managers reduce their carbon footprint through its Club programme

Bath & North East Somerset Council in the United Kingdom has installed smart LED carriageway lighting that automatically adjusts to light and traffic levels

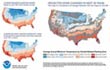

The United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and the American Public Gardens Association are mounting an educational exhibit at Longwood Gardens showing the link between temperature and planting zones

The energy-efficient Crowne Plaza Copenhagen Towers hotel is powered by renewable and sustainable sources, including integrated solar photovoltaics and guest-powered bicycles

El Hierro, one of the Canary Islands, plans to generate 80 per cent of its energy from renewable sources

The green roof on the Remarkables Primary School in New Zealand reduces stormwater runoff, provides insulation and doubles as an outdoor classroom

The Weather Info for All project aims to roll out up to five thousand automatic weather observation stations throughout Africa

SolSource turns its own waste heat into electricity or stores it in thermal fabrics, harnessing the sun's energy for cooking and electricity for low-income families

The Wave House uses vegetation for its architectural and environmental qualities, and especially in terms of thermal insulation

The Mbale compost-processing plant in Uganda produces cheaper fertilizer and reduces greenhouse gas emissions

At Casa Grande, Frito-Lay has reduced energy consumption by nearly a fifth since 2006 by, amongst other things, installing a heat recovery system to preheat cooking oil

Updated: May 15th 2015