Tiempo Climate Cyberlibrary

Malaria in Cotonou, Benin

- Tiempo archive

- Complete issues

- Selected articles

- Cartoons

- Climate treaty

- Latest news

- Secretariat

- National reports

- IPCC

About the Cyberlibrary

The Tiempo Climate Cyberlibrary was developed by Mick Kelly and Sarah Granich on behalf of the Stockholm Environment Institute and the International Institute for Environment and Development, with sponsorship from the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency.

While every effort is made to ensure that information on this site, and on other sites that are referenced here, is accurate, no liability for loss or damage resulting from use of this information can be accepted.

|

Krystel Dossou describes how climate change could affect malaria prevalence in the city of Cotonou in Benin. |

| He outlines the social and economic impacts of malaria in Benin, explaining how poor women and children are most vulnerable and describing two possible future scenarios. Key measures to prevent the spread of malaria and recommendations for city officials and researchers are detailed. | |

| The author is a programme officer at OFEDI, a woman’s environmental non-governmental organization in Benin that works on energy management and rural development. | |

Benin usually experiences alternating dry and wet periods, but global warming could modify rainfall patterns with dry periods lasting one to two months longer than in the past, particularly in northern areas. Agriculture, which is largely dependant on rain, will be affected. Forestry, water resources, health, the energy sector and the coastal zone are also vulnerable. The government of Benin has identified droughts, floods, sea-level rise and late and violent rains as the main climatic risks.

Cotonou is the economic capital of Benin as well as its largest city. Its official population count was 761,137 in 2006, although some estimates suggest the population may now be as high as 1.2 million. The city lies in the southeast of the country, between the Atlantic Ocean and Nokoué Lake. It is a low-lying city, vulnerable to increases in sea level, floods and coastal erosion. Number of people without access to clean water in Cotonou are estimated to be 13,000, whereas nearly 219,000 inhabitants are defined as poor, with an income of less than 165,000 Franc CFA a year.

Environmental conditions, particularly the presence of important swamps, strongly influence public health. Considerable volumes of soiled water drain into Nokoué Lake through the main city sewers. Oil pollution also goes in the lake along with waste from the Dantokpa Market. The Ouemé River pollutes the lake still further by bringing in pesticides, heavy metals and lots of organic matter and chemical and microbiological pollutants.

The importance of malaria in Benin

Malaria constitutes a major public health problem in Africa, particularly in Benin where the disease occurs all year round. Malaria is particularly prevalent in areas subject to flooding and one immediate consequence of an increase in flood frequency is the increase in mortality due to malaria. Malaria is the reason for 34 per cent of medical consultations and 20 per cent of hospital admissions. It is the principal cause of mortality in Benin, causing more than 1000 deaths per year.

The economic implications of this are enormous. Severe malaria requires admission to hospital, but those less sick still require help, usually to the detriment of their own or their helpers’ income generating activities. An individual can contract malaria on average three to six times per year depending on how effective his strategies are to fight or prevent the disease. The costs of treatment are considerable. Thus the direct and indirect costs relating to the disease are huge.

| Commune | 1996 | 1997 | 1998 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cotonou I | 7,169 | 6,936 | 5,754 | 6,574 | 5,214 | 5,138 | 6,759 | 6,756 | 5,896 | 56,196 |

| Cotonou II | 7,532 | 8,232 | 5,804 | 7,995 | 9,062 | 8,219 | 10,983 | 13,895 | 9,221 | 80,943 |

| Cotonou III | 1,814 | 3,130 | 2,389 | 11,973 | 15,770 | 14,474 | 17,339 | 20,251 | 17,297 | 104,437 |

| Cotonou IV | 2,206 | 2,131 | 1,548 | 2,808 | 3,103 | 5,651 | 7,108 | 7,789 | 5,258 | 37,602 |

| Cotonou V | 15,260 | 14,051 | 13,317 | 27,270 | 23,098 | 24,939 | 34,067 | 30,521 | 16,199 | 198,722 |

| Cotonou VI | 47,050 | 48,468 | 40,139 | 30,002 | 32,492 | 32,935 | 30,777 | 33,653 | 33,546 | 329,062 |

| The whole of Cotonou | 81,031 | 82,948 | 68,951 | 86,622 | 88,739 | 91,356 | 107,033 | 112,865 | 87,417 | 806,962 |

Malaria’s main victims are women and children under five years old from poor families for whom treatment is too expensive. In 2001, some 118 out of every 1000 inhabitants had the disease. This incidence was higher for children, with 459 out of 1000 children under one year and 218 out of 1000 children between one and four years having the disease. Children are particularly vulnerable to malaria because they easily become weakened by diarrhoea and vomiting.

Malaria is endemic in Cotonou. More than 800,000 cases of malaria were treated between 1996 and 2004. The years 2002 and 2003 showed the highest number of malaria cases while 1998 showed the lowest. Times of high prevalence tend to coincide with particularly rainy periods. Indeed, precipitation in Cotonou seems to increase the number of recorded malaria cases. After periods of rain, locals notice a remarkable increase in the number of malaria cases, perhaps because conditions for the spread of mosquitoes that cause malaria are more favourable. Morbidity tends to peak one to two months after peak rains. This knowledge can be used to plan optimal strategies to fight the disease.

Some parts of Conotou are more vulnerable than others. For example, areas bordering Nokoué Lake in the north of Cotonou have more cases of malaria. Locals observe storms of mosquitoes rising from Nokoué Lake and moving to Cotonou and Abomey-Calavi at about seven o’clock every evening once the city lights are on. There are also swamps in the north of Cotonou that affect vulnerability to malaria and where population density is high due to cheap house rental costs.

Concerns about malaria led the government to start a five-year programme (from 2001 to 2005) to "roll back malaria" in Benin. This aimed to half the mortality and morbidity due to malaria. Unfortunately, the "roll back malaria" programme did not integrate climate change into its planning, so all efforts made could be wasted.

Malaria and climate change in Benin

Climate change predictions suggest temperature increases of between one and 2.5 degrees Celsius by the year 2100. An increase in temperature could lead to the expansion of ecological zones suitable for the Anopheles mosquitoes that carry malaria. Average temperatures of higher than 16°C and 18°C are also favourable for the malaria-causing parasites Plasmodium vivax and Plasmodium falciparum, respectively. Climate change could, therefore, exert considerable influence on the number of malaria cases, especially when higher temperatures are maintained over long periods.

|

|

Cotonou, Benin

© mrfs.net |

Other factors such as the length of the wet season or rates of evapotranspiration could also be important. Models predicting changes to the length of the wet season vary. Some suggest the dry season will increase from six to seven months in length each year, whereas others suggest it could decrease to five months each year with the wet season increasing in length. In addition, a temperature increase of one degree Celsius could increase evapotranspiration rates from six to eight per cent. Higher temperature increases will increase evapotranspiration still further.

Conditions favourable for the spread of mosquitoes are increasing, and combined with increasing population numbers, this is likely to lead to continuing increases in cases of malaria unless public awareness increases and living conditions improve. Illiteracy is a key problem in this context.

Scenarios for climate change health impacts in Cotonou

Cotonou’s population is estimated to reach 1.2 million by 2025. Much could happen in this time. The worst-case scenario sees bad management and corruption leading to the failure of strategies implemented to tackle epidemics. There could be an increase in suitable sites for mosquito larva in areas prone to flooding and child morbidity rates could increase. Inadequate provision of health centres, poor hygiene, poor sanitation system provision and privatisation of medical services could all help increase the prevalence of malaria.

A more optimistic scenario is that the strategies used to fight or prevent epidemics are more successful. Activities planned under the environment ministry and city officials prove effective. Mosquito larva breeding sites are controlled, swamps are eradicated and fewer chemicals are needed to control mosquito populations. Impregnated mosquito nets are commonly used and treatment costs fall. As a result, malaria infection rates are reduced and child morbidity rates fall.

Measures to prevent or reduce malaria

Although mosquito nets are an extremely efficient way to prevent mosquito bites, they are not commonly used. Many parents can not afford to buy mosquito nets for all their children, so children share nets and thus find themselves lying with their skin up against the nets and, therefore, exposed to mosquito bites. Many children in Cotonou’s poorest areas just sleep on mats without nets, and where nets are used they are often badly maintained and perforated so no longer offer protection against mosquitoes. Acquiring nets is costly, though mothers with children under five years old are helped in this regard.

Self-medication is commonly used to fight malaria but it is not very efficient because it tends to treat symptoms rather than help with a cure. Many people take pills imported from Nigeria, which are often stored and handled in bad conditions. Removing sanitation structures can help, as can using sanitation structures in homes or nearby when malaria risks increase.

Many other health issues can aggravate malaria, including anaemia, severe respiratory infections, diarrhoeal diseases, skin infections and malnutrition. Environmental factors, such as how waste is managed, are also important. This includes the management of solid waste, biomedical waste and sewage in addition to drainage systems for rainwater. Cotonou produces nearly 400 tons of waste a day, some of which fills up swampy areas which can then be built on, but 61 per cent of which is badly buried or incinerated.

Suggestions

The long-term consequences of malaria will be greater if no adequate prevention measures are taken to limit malaria risks. Better awareness amongst national actors on the links between climate change and human health is necessary.

National authorities in charge of the public health system must plan ahead, taking knowledge of traditional medicine into account and following up on existing epidemiological and meteorological data in order to plan better. The district authorities of Cotonou and civil society must put extra effort into waste elimination and cleaning the environment of those most vulnerable to malaria. This includes improving management of rainwater and other waste and waste water. Environmental education needs to get better and the use of mosquito nets impregnated with insecticides must be promoted throughout the year. The capacity of non-government organizations working on climate change adaptation and development issues needs building. Adaptation projects to reduce social vulnerability to climate variability and climate change must be implemented.

Research capacity and the supply of equipment needs improving, including research capacity on traditional medicines. Researchers must work to improve and share their understanding of climate change impacts on malaria and other diseases, and adaptation measures appropriate for the Benin context.

Acknowledgement

This research was conducted under the Capacity Strengthening of Least Developed Countries for Adaptation to Climate Change Programme. Special thanks to Bokonon Eustache and Dr Glehouénou- Dossou who helped compile the French report on which this article is based, and to Hannah Reid for her assistance.

Further information

Krystel Dossou, Organisation des Femmes pour la gestion de l’Energie, de l’Environnement et la promotion du Développement Intégré, 04BP 1530 Cadjêhoun, Cotonou 04, Bénin, West Africa. Fax: +229-21350632. Email: krystod7@yahoo.fr.

On the Web

A number of World Health Organization publications on climate change are available.

Bright Ideas

General Electric plans to cut solar installation costs by half

Project 90 by 2030 supports South African school children and managers reduce their carbon footprint through its Club programme

Bath & North East Somerset Council in the United Kingdom has installed smart LED carriageway lighting that automatically adjusts to light and traffic levels

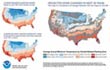

The United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and the American Public Gardens Association are mounting an educational exhibit at Longwood Gardens showing the link between temperature and planting zones

The energy-efficient Crowne Plaza Copenhagen Towers hotel is powered by renewable and sustainable sources, including integrated solar photovoltaics and guest-powered bicycles

El Hierro, one of the Canary Islands, plans to generate 80 per cent of its energy from renewable sources

The green roof on the Remarkables Primary School in New Zealand reduces stormwater runoff, provides insulation and doubles as an outdoor classroom

The Weather Info for All project aims to roll out up to five thousand automatic weather observation stations throughout Africa

SolSource turns its own waste heat into electricity or stores it in thermal fabrics, harnessing the sun's energy for cooking and electricity for low-income families

The Wave House uses vegetation for its architectural and environmental qualities, and especially in terms of thermal insulation

The Mbale compost-processing plant in Uganda produces cheaper fertilizer and reduces greenhouse gas emissions

At Casa Grande, Frito-Lay has reduced energy consumption by nearly a fifth since 2006 by, amongst other things, installing a heat recovery system to preheat cooking oil

Updated: May 15th 2015